Love. Angel. Music. Baby. was the name of Gwen Stefani's debut solo album that was released in 2004, meaning it turned twenty years old recently. In those twenty years a lot has happened. For one, Gwen Stefani got called out for cultural appropriation because her troupe of backup-dancers “Harajuku Girls”, named Love, Angel, Music and Baby, apparently represented racist stereotypes. Journalists would compare the four backup-dancers to geisha or even puppets with Gwen Stefani as their puppeteer. It's no wonder they had made these comparisons: the backup-dancers acted as her entourage and were only allowed to speak Japanese in public which is just kind of weird since all four of them can speak English. Gwen Stefani has explained in the past that she is just a big fan of Japanese culture and fashion in Harajuku; she just tried to show her love for it to the masses by incorporating it in her music. This expression of love definitely is a bit misguided in my opinion, but I can't deny that her love is very genuine. She did make a beautiful analogy in her song Harajuku Girls, which is actually correct: "A ping-pong match between Eastern and Western."

|

| Gwen Stefani and the Harajuku Girls (November 14, 2004 courtesy of Getty Images via USA Today) |

Harajuku is a district in Tokyo that is well known for being fashion-forward, but this has only been the case since the 1960s. Until then the district used to house homes, schools, churches and shops for Americans during their occupation of Japan, giving it a strong international atmosphere which only grew bigger with the Tokyo Summer Olympics of 1964. For this event they transformed the remaining barracks in the area of what's now known as Yoyogi Park into an Olympic satellite village. The international atmosphere drew in young people from upper-class families with men dressed in a continental European style and women dressed like mods inspired by Twiggy. They were known as the "Harajuku tribe" (Japanese: 原宿族) and these fashionable people spent their spare time racing up and down Omotesandō which became known as Japan's Champs-Élysées. This tribe really put Harajuku on the map as a hip and trend-setting area for young people. After the Shinjuku-incident of 1969 (Japanese: 新宿西口フォークゲリラ事件, English: lit. Shinjuku-West-exit-folk-music-guerilla-incident) caused folk music groups to start performing in Harajuku instead, Harajuku truly became Tokyo's youth culture epicenter. These events turned the district into a place of transcultural flow and even fascination, giving birth to many unique fashion brands that are still alive and kicking, like Milk by Hitomi Ōkawa. These brands started out by operating completely from a small apartment in the district, meaning they designed, manufactured and sold from an apartment in Harajuku, dubbing them "condo creatives" (Japanese: マンションメーカー, English: lit. condo-maker). This practice is still done by young and upcoming designers today, but I do think they might have moved to cheaper districts.

|

| Fashion on the Streets in 1967 (Tokyo) from Shūkan Bunshun (courtesy of timesrip1925 on X) |

The next tribe to take over Harajuku was the An-Non tribe, referring to the readers of two new magazines: an・an (1970, originally Elle Japon until 1982) and Non-no (1971). The An-Non tribe was characterized by young women wearing layered clothing and flowy skirts in pastel colors. The two magazines were targeted towards young women and featured Harajuku's condo creatives' collections. The reason these women got turned into a subculture is that they were often seen walking around with one of those magazines in their hands looking for the spot where specific editorials were shot or tourist spots that were featured in a spread. It was around the same time that Japan National Railways launched their "Discover Japan - Beautiful Japan and me" campaign (Japanese: 「ディスカバー・ジャパン - 美しい日本と私」) to promote domestic tourism by train. The campaign was successful and saw a growth in both individual travelers and female travelers, among them the An-Non tribe of course since Non-no and an・an would feature food tours in every issue. With Harajuku really having turned into a bustling and fashionable district Mori Building Company ltd. decided to build a shopping mall there named Laforet Harajuku, which opened in 1978. They chose this name because it's the company's name in French.

|

| an・an (1970, courtesy of magnif) |

|

| An-Non tribe girls (courtesy of parody575 on X) |

Initially Laforet Harajuku housed high-end women's clothing brands, but these failed to meet the needs of the hip and trendy Harajuku crowd. The place that did meet their needs was the Central Apartment where many condo creatives operated from. In 1980 Mori Building Company ltd. made the decision to welcome condo creatives into Laforet Harajuku. This change was a great success and sales naturally soared. This coincided with the DC-brand boom which was from 1980 until 1987. DC-brand stands for Designer's & Character's brand meaning who has the management rights. For example, Rei Kawakubo still has management rights over Comme Des Garçons, making it a Designer's brand, but Marc Jacobs does not have management rights over Marc Jacobs, making it a Character's brand. It is said that Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto were one of the reasons for the DC-brand boom since their Paris collections from 1981 kickstarted a new fashion subculture named the Corvid tribe (Japanese: カラス族, English: lit. Raven tribe), referring to their all-black avant-garde attire. The Corvid tribe later inspired the Mode fashion style which is still popular today.

|

| Corvid tribe girls (1980, courtesy of sabukaru) |

In 1982, Olive started being published and had teenage girls as its target audience. This magazine had a very dedicated reader base that called themselves "Olive girls" (Japanese: Olive少女). Olive girls' overall style is characterized by the magazine's concept of "Lycéenne fashion", meaning they're heavily inspired by Parisian schoolgirl fashion (and only used Caucasian girls as models). Even though this was their idea, in reality it looked more like a free and playful style that can be categorized in three main styles: a girly style with a lot of frills, florals, ribbons and lace, a more androgynous boyish style resembling Western school uniforms and a style that uses a lot of patches, pendants and other accessories to adorn their outfit with. Their favored brands were Milk and Pink House because of their cute, girly and romantic styles that fit the vibe of Olive girls completely. It is thought that these girls were the pioneers of kawaii fashion and I tend to agree with this notion since this was the first time the idea of shōjo (English: girl) came to the forefront in fashion. The idea of shōjo is a big concept that is part of the groundwork of kawaii overall. In the end, girls (and their mechanical pencils) are the reason kawaii even exists as a movement.

|

| Olive issues 73, 114 and 158 (1985, 1987 and 1989, courtesy of ravie, ぴょん and leaphappy on Mercari) |

After Japan's bubble economy collapsed in 1992, its economy started stagnating and the Lost Decades began. Many Japanese people who came of age during this period tried to cling to their childhood because it was a more prosper time with them being spoiled by their parents. Those who expressed themselves through fashion did this by dressing in styles that would later be named Decora (Japanese: デコラ,derived from デコラティブ, English: decorative) and Fairy (Japanese: フェアリー系, English: lit. Fairy-type). Decora finds its roots with Tomoe Shinohara, a "talent" or TV personality that saw great popularity in the 1990s and the opening of Sebastian Masuda store 6%DOKIDOKI in 1995. Tomoe Shinohara's fans were called "Shinorers" (Japanese: シノラー) and mimicked her personal look, which included colorful shorts, sneakers, layered tops, a children's backpack and a lot of plastic accessories, and her hyperenergetic way of acting. 6%DOKIDOKI started off by selling vintage clothing, but later fully dedicated themselves to selling accessories and clothing fit for Decora. The style is not really that predictable since wearers will often create their own version of it based on stuff they like. This can be animals, specific colors, characters or monsters. Fairy style can be traced back to Sayuri Tabuchi's thrift and hand-made goods store Spank! which opened in 2004. Fairies were originally named "Spank! girls", but it was magazine Zipper that coined the named "Fairy." While these subcultures aren't the same, there is some overlap in the childlike look they try to create in primary colors (Decora) and pastel colors (Fairy) respectively. Clothing is usually bought in stores that stock vintage clothing sourced specifically from America: oversized t-shirts, bright sports jackets and knitwear were favored among them. These clothes were often used to upcycle, so they created new pieces with it. This creativity is what makes these subcultures so interesting. In both of them the use of accessories is crucial, but there is a difference. Decora is characterized by abundance so bracelets that cover the wearers arms, multiple rings and clips layered in the fringe are very common. Fairies will usually stick to a couple of statement pieces like a big bow or a toy attached to a necklace.

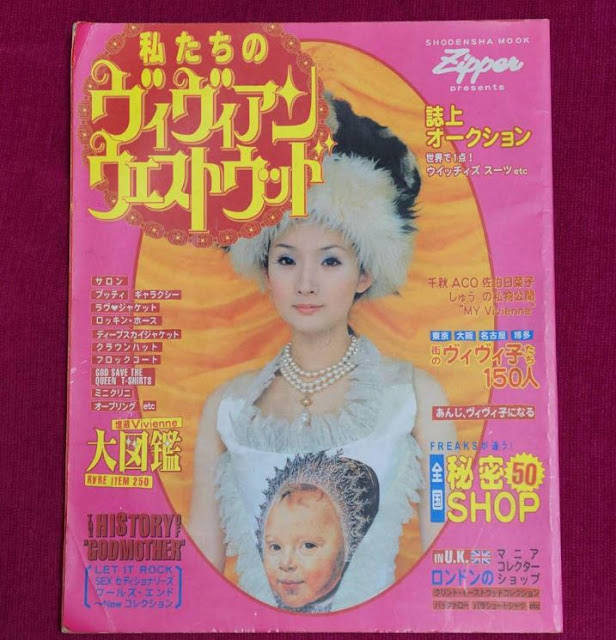

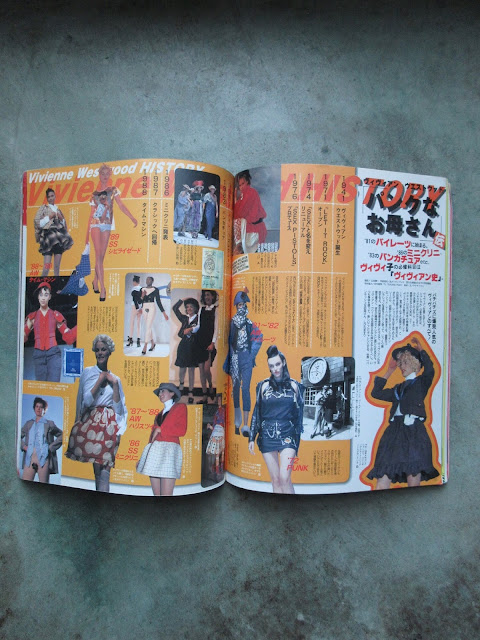

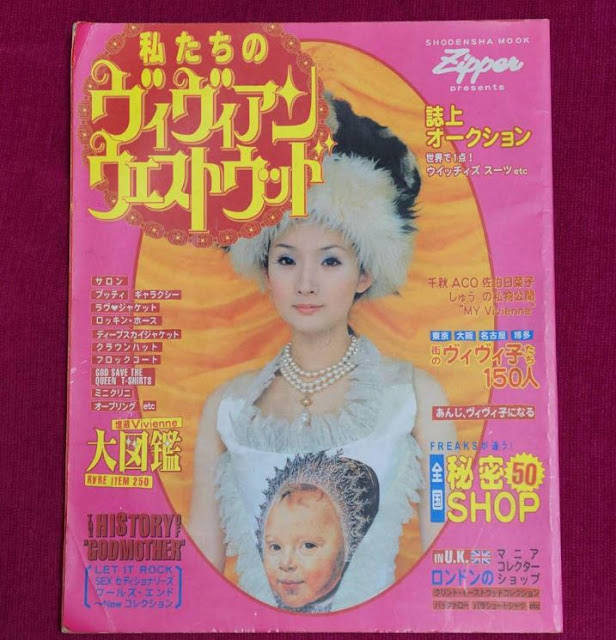

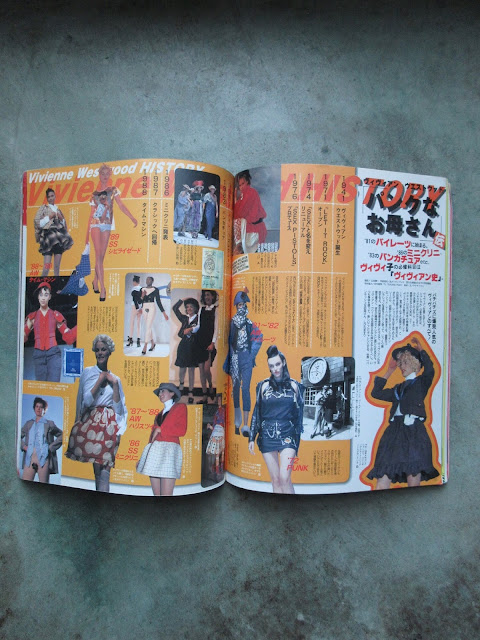

In the mid 1990s Vivienne Westwood struck a deal with Itochu Corp. allowing the company to import the brand to Japan. This was one of the best business decisions made since Japan would become Westwood's prime audience with it starting a true " Vivian craze." This reached its peak in 1998 when Zipper released a mook named Our Vivienne Westwood (Japanese: 私たちのヴィヴィアンウエストウッド) which, as the name implies, is centered around Vivienne Westwood's influence in Japan. In this mook they write various articles about Vivienne Westwood the person and the brand including the history of her runway shows and 250 rare items from her brand amongst others. Besides that it also features pictures of 150 Vivienne Westwood freaks or Vivi-ko (Japanese: , English: lit. Vivi-kid) who are donned in the brand from head to toe. This subculture is even featured in two manga by Ai Yazawa: Nana (2000) and Paradise Kiss (2000). In both manga characters sport a lot of Vivienne Westwood clothing, accessories and shoes with Nana from Nana wearing it in a punk style and Miwako Sakurada from Paradise Kiss wearing it in a sweet style. Nana's style got highlighted in Kera Vol. 58 which fittingly had Anna Tsuchiya as its covergirl.

|

| Our Vivienne Westwood (1998, courtesy of サルトのお店 on Mercari) |

|

| Our Vivienne Westwood "Vivienne Westwood HISTORY" (1998, courtesy of Ocha Books) |

In 2015 W. David Marx released a book titled "Ametora - How Japan saved American style", highlighting the cultural history of American traditional fashion as well as jeans and streetwear in Japan. This book focuses mainly on menswear, but I feel it could definitely be applied to womenswear as well. In my opinion, this globalization of fashion definitely had Harajuku as its epicenter in Japan with all the subcultures it has sprouted - and continues to sprout - the past sixty years. Of course, according to some people this could be viewed as cultural appropriation but I'd rather see it as cultural appreciation and even preservation in some aspects (e.g. Fairy-types preserving 1980s clothing and toys). Sure, Gwen Stefani should've treated her backup-dancers with more respect and should have allowed them to be more than the caricatures they ended up being, but she was one of the first people in the West to note the international bricolage that is Harajuku fashion. I believe this ping-pong match will never be over.

Thank you, and take care.

Comments

Post a Comment